Did Grandma Lie?

Season 27 Episode 23 | 52m 28sVideo has Closed Captions

Find out if family lore is fact or fiction in this special episode. One item is $85,000!

Find out if grandma lied about the family goods that include a 1900 Mark Twain letter, a ruby and diamond bracelet and a Babe Ruth & Honus Wagner signed baseball. Does the story of the show-topping $85,000 find really hold up?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding for ANTIQUES ROADSHOW is provided by Ancestry and American Cruise Lines. Additional funding is provided by public television viewers.

Did Grandma Lie?

Season 27 Episode 23 | 52m 28sVideo has Closed Captions

Find out if grandma lied about the family goods that include a 1900 Mark Twain letter, a ruby and diamond bracelet and a Babe Ruth & Honus Wagner signed baseball. Does the story of the show-topping $85,000 find really hold up?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Antiques Roadshow

Antiques Roadshow is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

ANTIQUES ROADSHOW 2025 Tour!

Enter now for a chance to win free tickets to ANTIQUES ROADSHOW's 2025 Tour! Plus, see which cities we're headed to!Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ So this actually... CORAL PEÑA: Which family stories about a treasure hold up?

My mother-in-law was right.

I'm gonna cry.

PEÑA: And which ones fall apart?

WOMAN: My mother-in-law was given to hyperbole.

(chuckles) PEÑA: Find out now in "Antiques Roadshow: Did Grandma Lie?"

♪ ♪ PEÑA: Some family stories about treasures that have come down through the generations are more fiction than fact.

A lot of things that we see at "Antiques Roadshow" come with little notes attached.

But unfortunately, a lot of the times, the information on the note is not accurate.

PEÑA: In this special episode, we've got some of the best stories about inherited items that we've ever heard...

Okay.

My mother told me that it was Marie Antoinette's, but...

Okay, well, Marie Antoinette never saw this bracelet.

Okay.

(chuckles) PEÑA: ...and reveal if their family lore is true or false.

That's remarkable news.

PEÑA: Like this treasure.

How old do you think it is?

Well, the story goes it was made by an Indian chieftain.

Uh-huh.

And it was given to our family, who came over from Scotland.

And I guess the chair goes back pretty far.

It's been passed down through the family, and they lived in the colonies, and it came to New Buffalo.

And I can go back five generations with photographs of all of us being rocked in it.

Were you rocked in it?

Yes.

My daughters were rocked in it, as well.

Who is this handsome character?

This is my grandfather, and he wrote a letter a few years before he passed away telling about the history of the chair.

I'd like to read just a, a little bit of it.

Your grandfather wrote, "I have fond memories of the chair.

"It sat in the sitting room of my grandparents' farm home.

"I loved my grandmother very much, "and as a child, "she used to rock me in the chair.

"Also, she would tell me that "when my feet would touch the floor, "she wouldn't rock me anymore.

And secretly, I hoped that my feet never touched the floor."

Yeah.

Very, very sweet.

So the family history takes you back four or five generations, it sounds like.

And...

Yes.

One thing to keep in mind is you don't find the age of an object by adding up the lifespan of those people.

When you look at generations, people may have had children when they were 20 years old.

Right.

So going back four or five generations might only take you back to the late 19th century rather than to the 18th century.

Okay.

Okay.

I don't know if you ever noticed, but the way the rocker is attached to the front legs...

Yes.

...is with a bolt and a nut.

That's modern technology.

These were assembled in a factory setting, and you could order them from catalogues.

And how do you refer to this chair, at home?

The, the old hickory rocker.

The old hickory rocker.

Yeah.

What, what's it made of?

I, I have no idea.

It's hickory.

Is it?

Okay!

(laughing): It is hickory.

All right, we got that right.

(both laugh) Now, there was a North Carolinian who moved to Indiana, which I think is where part of your family's from.

Yes.

And he started a company called the Old Hickory Chair Company in the 1890s.

Okay.

Now, this chair is not marked.

Right.

But it fits perfectly into what they were making at that time at the Old Hickory Chair Company... Wow.

...in Indiana in the 1890s.

Your grandfather, do you remember when he was born?

Around... 1909 was when he was born.

Okay.

So this might be 1915, then.

Yep, yep.

Something like that.

Well, that's right in the period when Old Hickory Chair Company is producing lots and lots of chairs like this.

Now, what I love about this is, your family history says that this was made by an Indian chieftain and passed down through the family.

(laughing): Yes.

Well, that's exactly the kind of history that they were trying to evoke with these chairs.

Do you have any idea what it's worth?

No idea, no clue.

Well, they made a lot of these, but they have come back into vogue.

It's probably, at auction, I would estimate it at $1,000 to $2,000.

Wow!

I'm really surprised, actually, that it's not older.

WOMAN: My grandmother saw it in a jewelry store window in San Francisco in the early 1920s or before, and she was quite taken with it, and she bought it.

And she called it a poison dart ring, but apparently there are no darts involved.

How did she come to the idea that it's a poison dart ring?

It has a little hole in it, through which...

Apparently, there used to be a button, but she thought that a dart would go in, and you'd push down on the top of the ring... (chuckles) ...and that would shoot the dart into your enemy, who you were shaking hands with.

Wow.

She was told it was worn on the thumb.

Mm-hmm.

And she was told that Cellini made it for Queen Isabella.

Oh.

However, Queen Isabella died when Cellini was four, so we don't quite believe that one.

Have you ever showed this to anybody, gotten any opinions?

I showed it to someone who thought that it was a Renaissance piece... Mm-hmm.

And gave me a jewelry value, but they didn't know anything else about it.

They'd never seen anything like it.

I think that it's not a Renaissance ring.

I think it's a Renaissance Revival ring.

The Renaissance Revival took place in England and Italy and other parts around Europe from between around 1860 through around 1900.

It's sort of a reaction to industrialization.

It's a return to an older aesthetic, when things were simpler.

We feel that it's probably made in England.

I don't think it shoots poison darts, but it is a poison ring.

Or it's made in the form of a poison ring.

What we're looking at here is an 18-karat-gold ring, which is in the shape of a salamander or maybe some sort of a frog.

And it's set with rose-cut diamonds of different cuts.

There's round ones and triangular ones and a pear-shaped one.

And then it's got table-cut diamonds, and these are all diamond shapes that ha, would have been used in the 15th, 16th century, when Renaissance jewelry was being made.

But the ring is really heavy.

It's very heavy gold.

Mm-hmm.

And the Renaissance jewelry is much lighter.

It's hollowed out.

Now, it does open.

The frog, or salamander, has been enameled nicely on the inside with colored enamels.

If I turn this ring over, we can see champlevé enamel underneath, done in sort of an Arts and Crafts pattern... Mm-hmm.

...where there's been a coil of green enamel and then leaves enameled in with the blue over here.

I'm not sure that it's a thumb ring.

I suspect it might be a gent's ring.

Men in the 19th century wore more jewelry than in the 20th century.

Or there's another possibility: women would wear rings on the outside of their gloves.

Do you have any idea now of what the material value of the piece was?

Someone told us that it was, that the jewelry value, just the stones and the gold, was about $1,000.

Just because it's so exciting, it's such an interesting form, it's exotic, it's a wild animal... Yeah, it's really fun.

People like wild animal jewelry.

We feel that, at auction, this ring would take an estimate in the range of $5,000 to $7,000.

Oh, really?

Oh, that's great.

Yeah.

It's not for sale.

WOMAN: This is a mystery for me.

It is something that my husband and I inherited from his aunt.

Aunt Jean and her husband lived in Eureka.

APPRAISER: Mm-hmm.

And they did a lot of collecting, and collected art glass, and this was in her collection.

Mm-hmm.

My husband called it a princess cup.

It was, like, one of his favorite things.

Right.

I believe he called it a princess cup because probably his aunt called it a princess cup.

Okay.

But we really know nothing.

I know nothing about it.

My husband, unfortunately, has passed away.

I'm sorry.

Um, today's his birthday, though, so I just feel like it's all meant to be that we're here with one of his favorite things, and I'm going to find out what it truly is.

And we are so fortunate to be able to see one of the things here today that he really, really did treasure.

So thank you very much for bringing it to us.

You mentioned it was called colloquially the, uh, princess cup.

Yes.

Affectionately known.

The thing with this being a cup, of course, is that it has lots of holes in it.

Yes, that's problematic.

It's known as a zarf-- that's spelt Z-A-R-F.

It's a very unusual-sounding word, but it's actually coming from the Arabic for "envelope."

Mm.

Which, basically, you know, to enclose something.

Okay.

And as we can see, because of the holes we mentioned a second ago, it's not going to work as a cup as it is.

Correct.

So it's going to have supported a glass that would have been used to hold coffee.

It's essentially a coffee glass holder.

Really?

Yeah.

Wow!

Coffee was introduced into-- and this is where you sort of find out where it's from-- into Istanbul in the mid-16th century.

It's an Ottoman zarf.

The Ottoman Empire spread across the Near East.

It incorporated Syria, parts of Iran, Iraq, and so on and so forth, until the Ottoman Empire fell in the 1920s, and so this was made during the Ottoman Empire, probably towards the end of the 19th century.

It's made of 18-karat gold.

It's enameled, and it also has a profusion of these old-mine-cut diamonds.

So quite clearly, for a coffee cup, it's exceptionally beautiful and handsomely crafted.

The reason being is that, just with tea and with other drinking cultures across the world, coffee was seen as something that was still imbued with a lot of ceremony in a, in, uh, sort of Ottoman Turkey and elsewhere, in Iran and so on.

And so the receptacles to hold the drink could have been incredibly lavish and well-made, such as this one.

This would have probably been used, even though it is such a luxury, high-status thing.

It would have obviously shown the status of the owner.

They were often also given as gifts to various courts and other high-status individuals within Europe and elsewhere.

So it's a beautiful object.

Yes, I wouldn't, I would never have guessed that that was its purpose.

At auction, I would estimate this to sell for between $3,000 and $5,000.

(mouthing, laughing) Wow.

Wow.

I'm... (laughing) ...really surprised.

Pat would be so happy.

(voice breaking): That's...

It's, it's a, it's a lot of... That's amazing!

It's a lot of money.

It's, for, to hold a cup of coffee.

Exactly.

It's beautiful.

It is.

It's really exquisite, and, uh...

Thank you so much.

Well, thank you.

Thank you for bringing it on.

I have a photograph of Billy the Kid.

He stayed with my husband's great-uncle when he was hiding out in St. Louis.

Which one is him?

25?

Center.

Right here, in the center.

Oh, wow.

Supposedly.

So, we'll see-- supposedly.

She claims this is Billy the Kid.

WOMAN: I think he was here in St. Louis with a family about 1875, 1880.

APPRAISER 2: The first thing I would tell you is that the photographic paper is a, is a silver gelatin paper... Oh, okay, okay.

...that was not made before about 1890.

Okay.

So, the photograph... Really?

...is...

So you can tell that?

Okay.

Yes, yeah.

And here's the other thing: If you're an outlaw, the last thing you want to do is stand and have somebody take your picture...

Yes, yeah.

...so somebody can recognize you.

There's no chance that I would be making a mistake...

There's zero chance that it's Billy the Kid.

Really?

Okay.

As in none, zero, nada, zip, nothing.

(laughing): I get that.

Okay.

WOMAN: Well, we call it a sugar shaker, but I don't know if that's the right name.

It's an old family piece.

In Findlay, Ohio, there were a number of companies that made all different kinds of Findlay glass, and this particular one was made by the Dalzell Company.

It's about 1889.

Now, the, uh, sugar shaker is probably a more modern version of what they referred to as a muffineer.

Ah.

And this did have powdered sugar, and you would powder your muffins with it.

So that would be the accurate name, muffineer.

Well, sugar shake, shaker is absolutely acceptable.

You'll hear it referred to in, in two different ways.

This little tiny piece is $850.

Oh, oh, you can't be serious.

I'm serious.

Oh, my word.

WOMAN: This is a teapot that my great-grandfather collected.

APPRAISER: Mm-hmm.

And it's just been passed down through the family.

Mm-hmm.

So I don't really know much more about it.

Think it's from China.

(laughs) Oh, ho, okay.

Um...

Right, actually, it's from Japan.

Oh, okay.

Yes?

They are made of silver and then filigree, and then within that, they, uh, put the translucent colors on it.

Oh, okay.

The, uh, details are exquisite.

So many things to look at.

It could look like ivory.

But you don't think it's ivory.

It's bone.

Oh, okay.

And it was made in late 19th century, maybe about 1890s.

All right.

And it has a name.

It...

It has a maker's name.

It was in, uh, J, Japanese, I guess, also.

Yes, it's Japanese name.

(laughing): I, I couldn't read it.

Yes, it's a, um, famous maker's name called Hiratsuka.

Okay.

Yes, I think at auction, it should bring $20,000 to $30,000.

Oh, my gosh!

(inaudible) (laughing): Yeah, we weren't expecting that much.

Oh, yes.

So enjoy it.

Oh, wow, yeah, definitely don't break it.

(laughing): No, don't break it, yes.

(laughing) WOMAN: They came from my father's family, and I'm not 100% sure where they came from.

(chuckles) Now, somebody wrote a note about them here.

My grandma wrote that, and she must have done some research on it to try to find out what they are.

She wrote here that these are rare; they're Worcester; they're in scale blue, she says; and she puts the dates there of the Dr. Wall period of Worcester.

A lot of things that we see at "Antiques Roadshow" come with little notes attached, or sometimes information is actually written on the porcelain.

And this can be a good thing to do, to put a little note inside something once you've had it correctly identified.

But unfortunately, a lot of the times, the information on the note is not accurate.

And I think what your grandmother did, she saw something at Marshall Field's department store, if this was done in, let's say, the 1930s.

At that time, Marshall Field's had a fabulous antiques department-- great, authentic things, mostly imported from Europe.

And she would have seen a first-period Worcester vase or something that looked like this, but she's unfortunately misidentified it.

Okay.

The first period of the Worcester Porcelain Company-- which still exists, by the way, it's called Royal Worcester today-- was referred to as the Dr. Wall period.

We kind of stopped using that term because it's not quite accurate.

Dr. John Wall was there, but the first period, as we can define it, is a little different in date.

In first-period Worcester, scale blue has this deep cobalt blue color that you can see in the background with a kind of scale pattern on it, like a fish scale.

That's what I wondered.

Very subtly.

The style of it, too, is not quite Worcester.

Okay.

Worcester did make vases of more or less this shape, with panels painted in the center, but the handles are quite wrong.

And what it's made of.

First-period Worcester is made of a kind of porcelain that we call soft paste porcelain.

This is hard paste porcelain, which is very sort of glassy-like, very white and shiny.

So that is enough to tell us...

Okay.

...it's not first-period Worcester.

But in any event, what we've got are a pair of French porcelain vases.

They're a really nice quality pair.

Probably made 1850s, '60s, something like that.

They're in good condition.

They're also really nicely painted, but they're not, I'm afraid, anything of this.

Okay.

In terms of value.

I would say, in a good antique shop today, they'd be priced at at least $1,200 and maybe $1,500 for the pair.

Okay, okay.

If they were Worcester of the first period... Mm-hmm.

...they could be $7,000 to $8,000, something like that, or more.

But they are great vases in their own right.

Okay.

All right, thank you very much for coming today.

Thank you.

Actually, my great-uncle is an archaeologist/optometrist, and it came from his basement, which, he used to have all kinds of good things in his basement.

Oh.

(chuckles) And where did he get it?

He did it-- he said that he got it from a dig somewhere in New Mexico.

And that's all I really know about it, so... Well, it's not from New Mexico.

It's never been buried.

Oh, my.

(laughing): And... And it, and it belongs in one piece like this.

Okay.

It's a Hopi kachina.

And the top part's called a tabletta, which had been taken off or come loose.

Originally, it had feather plumes.

It was probably made sometime between 1900 and 1920, something like that.

Okay.

It's a beautiful piece, and do you know what these are?

I don't know enough about them, no.

These are to educate the children and young people in the tribe about the beings that carry prayers to the gods or to the heavens, in, in our culture, is what we would say.

They learn who the dancers are that come out in the plazas at these different ceremonials.

This is the way they learn how to identify 'em.

And so they're important to the culture, but they are educational tools.

If I saw this one for sale today at auction, even in this shape, with the feathers gone, which is okay, that's not a problem.

But even with the tabletta loose, probably $2,500 to $3,500.

(chuckling): Oh, my gosh, I let my kids play with this, so... (chuckles): Hey, that's what I can tell you.

Thank you very much, I appreciate it.

That's awesome.

Thanks, Colleen.

(laughing) None of anything anybody told me was right about any of it.

My father's family is originally from Newburyport, Massachusetts, and this document is my great-great-great- grandfather's.

He was a man of color living in Newburyport, Massachusetts, and this document's allowed him to travel to the South, where he had relatives.

It's dated 1815, and my father passed that down to us and we treasure it.

And this we call the grandfather's chair.

Yes.

Now, we're not sure which grandfather.

We know it was my father's grandfather, but if it was his father, we don't know.

There are various dates under here: 1850-something, 1700-something.

We just always sat in it.

You can see the bottom is quite worn.

And you sat on this chair?

I sat on this chair.

My father sat on this chair.

Probably his father, as well.

You can see it's taken quite a beating.

It's a great heirloom.

This is a passport.

Okay.

It's very straightforward document, and as we see, it's from Essex, town of Newburyport, it's notarized by a man called Woart, W-O-A-R-T. Mm-hmm.

And he is justice of the peace.

It's got his seal...

Yes.

...and signature, and as you said, the date of 1815.

The date.

It's suffered a little bit of bloom and damage, couple of holes here.

But essentially, it's a great historical item.

Ooh, thanks.

Here you have the respect given to a man of color in the North in 1815.

Right.

It's very early.

And the other interesting thing is, yes, indeed, this is an absolutely genuine Massachusetts-made Windsor chair.

It is?!

Oh, my goodness.

And as you've said, it's got some... (laughs) Some repair.

It's had its feet cut down, but it is a child's chair.

Yes.

At auction, the whole package is worth $2,000 to $3,000.

Okay, all right.

But obviously, it is of...

It's... ...tremendous family significance.

Yes, value.

Well, we treasure both items, and this chair has... A lot of bottoms have sat on it, and we love it and we hope to just keep passing it down.

Yes.

MAN: This pistol is, uh, one my grandfather found out on his ranch, and he had a man named Brigham Hamilton with him, and this man was a member of Butch Cassidy's gang at one time.

And this Brigham Hamilton told us that when they used to ride down this trail, they'd have several pistols in their saddlebags, because the pistols in their holsters would fall out when the posses were chasing them.

And since this was so close to their hideout, he figured this gun belonged to somebody in Butch Cassidy's gang.

When was this that he found this pistol?

Um, about 1920.

1920.

Yes.

There's a picture of Brigham Hamilton with Butch Cassidy that we had found in a book.

That would be Brigham Hamilton there.

On the left.

And of course, Butch Cassidy's on the other side.

So we made a copy of it and got my grandfather's story and put it on there, so we'd have it always.

That's a very interesting story.

As you know, Butch Cassidy was one of the famous bank and train robbers...

Right.

...um, in the 1890s, out here in the West.

The pistol you have is a Colt Single Action Army revolver.

It was first produced starting in 1873.

The production went all the way through just before the Second World War.

Your pistol is in fairly good condition.

There seems to be a carving over here in the grip, and it appears to be some initials.

Do you think you know what they are?

It looks like, um, my grandfather's initials to me.

J.A.M.

With the story and everything else, I, I think it was a really interesting gun.

I did some research on it, though, on the gun itself, 'cause it's a serial number, uh, 252,000-range, and the gun was actually manufactured in 1903.

Okay.

So unfortunately, your story probably is not correct.

Oh.

The reason I know this is that Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid departed for South America in, in 1901.

Oh, okay.

And the last recorded raid of the gang was in July of 1901.

Okay.

But as such, I still feel that at auction, this revolver would bring about $1,500 to $2,000.

Okay, wow.

If the story was correct, I would say that the gun could've probably been worth $5,000 and upwards.

Oh, wow.

We think it originated in the Taunton, Massachusetts, area, and it's engraved with the name of the great-grandfather of, of mine who, whose son gave it to him.

Actually, it has the date that it was given, of May 1873.

This piece was made in San Francisco.

Really?

What we're looking at is a piece of gold quartz.

I'm gonna conservatively estimate it at auction for between $2,000 and $3,000.

Wow.

Incredible.

It was a friend of mine that owned it.

It belonged to her great-grandmother.

And the story goes that she supposedly made molasses in this.

It's probably going to sell for $300 to $500.

Wow.

(chuckling): Oh, my gosh, you're kidding.

Yeah.

And I don't think they ever had molasses in it.

WOMAN: I doubt it.

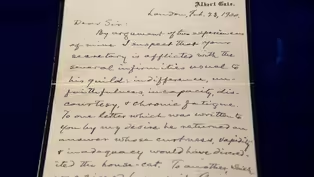

(all laugh) WOMAN: I brought a letter that was written by Mark Twain to my great-great-grandfather trying to get a student into the School of Osteopathic Medicine in Kirksville, Missouri, and trying to get a response.

I love this letter.

Like a lot of Samuel Clemens' letters, it's an angry, "I want to see the manager" kind of letter.

He just starts off full of rage.

The letter begins, "By argument of two experiences of mine, "I suspect that your secretary is afflicted with "the several infirmities usual to his guild: "indifference, unfaithfulness, incapacity, discourtesy, and chronic fatigue."

And then goes on to the business of, "I'm trying to get this guy into this school.

What can you do?"

And he actually does sign Mark Twain and not Samuel Clemens, which is interesting.

At, at this point, in most of his private correspondence, he would have signed Samuel Clemens.

A good saucy Twain letter sells for about $3,000 to $5,000 at auction, in today's market.

Great!

WOMAN: I brought a ring that was in my family for many years.

My great-great-grandfather immigrated to Milwaukee in 1864.

He was 19 years old.

He was an apprentice jeweler.

He started a family there, but then moved to Chicago, where he opened a jewelry store.

Had that for many years, I don't know how long.

And this was from his jewelry store.

It was given to my grandmother, who in turn gave it to my aunt.

Aunt Betty was very close with our family.

She would come to our house in Michigan and she came for Sunday dinner.

And she gave this to me when she was ill, uh, got, was getting older.

The story she told me was that Grandpa said these were a perfect match diamonds.

So I'd just like to find out what you think about that.

It's a lovely, lovely ring.

They are what we call an old European cut.

It's an older-style cut.

Now, today, the more modern stones that are cut, the facets slightly different.

These have open culets in 'em.

I measured the stones, and they are almost identically matched.

One stone I estimated weighs two carats, and the other weighs just slightly more, 2.05 carats.

The top stone is the stone that's slightly larger.

The color is very nice on 'em.

It's not a perfect color, but a very high color.

They're like an H to an I color.

So they're basically colorless to the human eye.

Mm-hmm.

In the sunlight, they would be extremely brilliant.

Mm-hmm.

They're very clean stones.

There is a slight chip on the girdle, which is the edge of the stone, on one of 'em.

Probably got hit on a sink or something.

It's a slight chip just on the very edge of the stone.

That could easily be polished...

Okay.

...and could be fixed.

When do you think he gave this to your grandmother?

I would say this was made in the early 1900s?

Well, they're certainly cut like they were from the early 19, they could be from the early 1900s.

The mounting looks a little later.

Okay.

So it probably was remounted at one time.

Did you ever have this appraised?

No, I've never had it appraised.

No.

If you had to venture a guess, what would you guess the valuation on a, on the piece is?

We... We thought maybe a couple of thousand dollars.

Okay.

The diamond market is v, very strong right now-- I would say that these two stones being matched, which also increases the value of the stones, because it's difficult to find two matching stones.

You can go through thousands of stones trying to find two stones that match.

These two stones in a retail situation today would easily be about $15,000 each.

(laughs) So you're looking at $30,000 for the two diamonds.

Oh, my goodness!

That's remarkable news, lovely, lovely.

(laughs) A little more than $2,000.

Yes, sir.

(laughs) Well, thank you so much.

WOMAN: My mother-in-law was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and she had a lot of interesting antiques and some interesting books.

My husband and I were looking through her things, and we found it in a, the kind of bag you get when you buy a card, and she had just put it in there.

(stammers): Had, I guess, forgotten about it.

And I know enough about books to know that, gee, if it's old, it might be rare.

And I knew enough about Walt Whitman to know that he self-published his own work.

He had some problems with copyright law.

He lived in Camden, which is where my mother-in-law's family had lived, and it's inscribed to her, I guess it's 1875, so it would be many- greats-uncles.

It is the, Walt Whitman's "Memoranda of the War."

Mm-hmm.

And when you open it to the title page, you see that it is published in Camden, 1875-76.

And he was sort of a revolutionary poet in the way of the type of poetry he was writing.

But, of course, why we're really looking at the book is not the title page.

Mm-hmm.

It's this first page here.

Right.

And it's a very, very nice inscription.

"For the firemen at the house, "corner of Fifth and Arch Street, Camden.

With best respects, WW," which, of course, is Walt Whitman.

Walt Whitman, yeah.

So tell me about the firemen.

The firemen would have been her...

I'm, I don't know my great-greats, but several-great-uncles.

My husband and his brother, because they were men, never really took the D.A.R.

membership or any of the antiques seriously.

And my husband's family lore was this Walt Whitman book.

And we were always told, "Well, if you ever need any money, there's always the Walt Whitman book."

(laughs) When you get into these books, one of the things you look for is, is the gold still bright?

Can you still read it?

Are the edges worn?

There's a little tiny bit of wear.

When you go through the book, a few of the pages, you said, are stuck together, but it's in very, very fine condition.

The other thing about this book, though, is, there was a remembrance edition of this.

Now, in the remembrance edition, which was the first edition, here you would have a portrait of Walt Whitman, and you would also have a little slip saying it's that edition.

So this actually is a slightly later edition of the book, but you have the great inscription.

Now, what have you done on price, have you looked it up?

Well, the family lore is that it could be worth anything from $100 to $10,000.

And I did look online, and I saw another Walt Whitman "Memorandum of the War," um, that was going for $8,000, but it was a first edition.

And since you now tell me it's not a first edition, I know that that makes a big difference.

The fact that it's not a first edition is a little bit of a detraction.

The fact, though, that it has a fabulous inscription... Mm-hmm.

...just adds to it.

Retail, it would be more a $10,000 to $12,000 book, Really?!

And that's even being a little bit on the conservative side.

If you don't mind, I'm gonna cry!

My, my mother-in-law's been dead for a while, and I just feel like I've justified her.

And I want all the men to listen, in my family to listen to this.

My mother-in-law was right!

Well, she was right...

I'm gonna cry.

It's wonderful.

And the inscription is what makes it.

It's a great inscription.

Mm-hmm.

And, uh, thank you for bringing it.

Oh, thank you.

If this wasn't inscribed, it might be of $800, $700, $500.

The story in the family is that it was made by my great-great-grandfather in Concord, Massachusetts, Cyrus Benjamin.

It's been in the living room of my mother's house and my house for, for as long as I can remember.

So family lore says it was made by Cyrus Benjamin.

Cyrus Benjamin.

About what time would that have been?

It would probably have been, we thought, about 1860, 1870.

Okay.

About the time his son had gone into the Civil War and he had a shop in the back of the house.

Okay, well, as sometimes can happen, family history is off by a generation or two here.

(chuckles) A table like this is generally referred to as a demilune card table, made in Eastern Massachusetts about 1800.

So 60 or 70 years earlier than family lore would suggest.

And before Cyrus Benjamin was born.

Exactly.

(chuckles) This table, though it's based on a Boston example of a demilune table, is likely made, if not in Concord, certainly in the Concord, Massachusetts, area.

That makes sense.

Without a doubt.

It'd be referred to as a Federal period card table.

It relates to Federal furniture.

It is a remarkably colloquial table.

And what does that mean?

Well, there's a lot of country cabinetmaker things that are going on.

All right.

Especially with relation to the inlay on this table.

Oh.

Which relates to a lot of Boston forms.

At the top of the dies here, you can see what I would refer to as a contrasting quatrefoil, very similar to a lot of furniture made in Concord, certainly.

What I like best, however, is the really delicate line inlay just below that, at the top of each leg.

You can see this wavy line inlay that sort of intersects a couple times and then ends in drops.

That's a great country example of a city form made with indigenous woods, like cherry on the top, and it excited us when we saw it because it's a good rarity to have a table made in that area of Massachusetts.

Good to hear.

In its current state, we'd estimate it, for auction purposes, at $3,000 to $5,000.

(chuckles) That will shock my brothers and sisters.

(chuckling) Well, good.

Wonderful to hear.

Yeah.

I appreciate that, thank you very much.

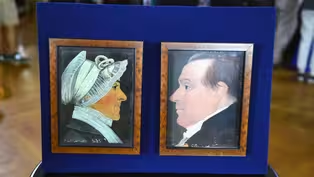

WOMAN: They came down from my mother-in-law, and we think they may be Benjamin Greenleaf, but I'm not sure of that.

My mother-in-law was given to hyperbole.

(chuckles) Ah.

And these came down from the family, and each woman brought it down.

So it's been handed down to daughter to daughter-in-law, okay.

(murmurs) Since you've had them, have you done anything to them?

The only thing we did was frame them.

And so, these are newer frames, then?

Yes.

And what did the original frame look like?

Well, the frames that my mother-in-law had, um, were really the kind that you would put on a, a, a diploma.

Those little black ones?

Uh-huh, okay.

Um, and they were falling apart.

Okay.

So that's why we had them... Let's start with dispelling any family hyperbole, an, any apo, apocryphal story.

(chuckling) These paintings are definitely by Benjamin Greenleaf.

Greenleaf, as you may know, was born in Hull, Massachusetts, in 1769.

And he really started painting when he was in his early 30s.

Before that, we don't know what he did.

He, he's one of those artists that we don't know much about, but we do know he was active for about a 15-year period between 1803 and 1818.

He was an itinerant painter, going from town to town, staying there until he'd either worn his welcome out or he's painted enough commissions that he, he was done.

(chuckles) Now, this painting is very typical of Greenleaf's work, because it's painted on glass.

It's a reverse painting.

Greenleaf took a piece of glass and painted the portrait on the back of the glass, and they're very fragile.

The gentleman was almost certainly by, also by Greenleaf, but it's on a panel.

It's on a piece of wood.

One of the things that Greenleaf was known for was painting these profile portraits and ba, and virtually filling the painting with the portrait.

And in fact, this one, I wonder, when it was reframed, if her bonnet really goes underneath the rabbet of the frame.

Oh, yeah, oh, interesting.

Now, here's the potential bad news.

Greenleafs, every one that I've seen, they're in those little crummy black frames.

(chuckling) So you might have thrown away the original frames.

In spite of the fact that the portraits are great, if they'd been in their original frame, they'd be even greater.

Greenleaf's work is really pretty rare.

There're, there're less than 60 of the, uh, these portraits known to have been done by him, probably because a lot of them broke, because they were glass.

Oh.

I would think that in this condition, in these new frames, the good presale auction estimate would be $5,000 to $7,000.

Wow.

Very good.

Now, if they were in their original frames, you might add a few more thousand, and they might have been worth $8,000 to $10,000.

I should also point out that Greenleaf did various sizes of these, so the bigger that they are, the, the more expensive they are, because they're more fragile.

It's been in my family since 1737.

APPRAISER: You tend to associate these as being late 18th century, early 19th century, so it's not quite as old as the family lore would have it.

(mouths) It's a very early form of traveling clock.

They're also sometimes called campaign clocks because they were associated with the military.

Okay.

I would put a retail value on it for between $3,000 and $4,000.

Wow.

(chuckles): Wow!

WOMAN: My great-great-aunt was a traveling companion to a very wealthy woman, Charlotte Cardeza.

They traveled the world for many, many years, and one of their voyages was on the Titanic.

Charlotte, my great-great-aunt Annie, and Charlotte's son Tom were dining when they got the call that the ship was sinking.

And they did survive.

They were on lifeboat number 19.

And what you see there was a cufflink that Tom wore.

After they were rescued, he had the cufflinks made into two rings, one for his mama and one for himself.

Later, he decided that he really didn't need this ring, and he would give it to my great-aunt, who supposedly, according to family lore, offered to give up a seat on the lifeboat for Tom.

Obviously, they all did survive, so they all got on the lifeboat, and it's been in the family ever since.

I think it's a really successful example of a conversion from a cufflink to a ring.

This piece really spoke to me, because of the quality of the stones.

We have a beautiful emerald-cut emerald in the center.

Based on the color and quality of the emeralds, my guess is that the origin is Colombian.

The top part of the ring, which was originally the cufflink, was made in 1910, somewhere in that period.

Mm-hmm.

Which makes sense.

Yeah.

Because we know that Tom was wearing these cufflinks in 1912.

The diamonds that frame the emerald are transitional-cut diamonds, between old-European-cut and old-mine-cut.

These transitional-cut diamonds are also typical of that period.

The band, constructed of yellow gold and platinum, was made later.

In the late teens, early '20s.

Oh, okay.

Where was Tom living?

Do you know?

Germantown, Pennsylvania.

That makes sense.

Yeah, right out of Philadelphia.

Mm-hmm.

My guess is that this conversion was done right in Philadelphia.

Mm-hmm.

Unfortunately, it's not signed.

Okay.

So we don't know exactly who made it.

Who, okay.

I love the inscription-- so Tom had the jeweler inscribe on the side, "Saved from the Titanic," with the date, April 15, 1912.

As well as... "Tom" and "Mama."

This pierced band is exquisite craftsmanship.

It is so beautiful, it is so well done, and it's really unlike anything I have ever seen.

Okay.

Especially when paired with such a fine Art Deco cufflink.

At auction today, I would expect it to bring somewhere in the $6,000 to $8,000 range.

Hey, wow.

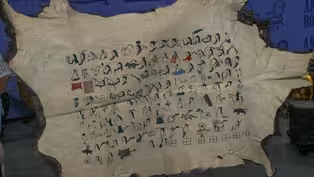

All right.

WOMAN: This is my great-great-uncle's Sioux winter count.

And we have a picture of him right here, is that right?

Yes, his name was Moses Red Horse Owner.

Moses Red Horse Owner.

Yes.

And he lived to be how old?

He lived to be 72 years old.

And when did he die?

1908.

And we have here in this book some drawings, correct?

Yes, yes.

And you're calling that a winter count.

Yes.

For people out there that don't know, what is a winter count?

Well, the Sioux were a history-conscious people, and they liked to record one great event that happened during the year.

The tribal elders would meet in the wintertime and, uh, sit around and tell, uh, the historian to be sure and record this in his mind.

So they did one event per year, correct?

Yep, per year, yes.

So in a sense, this is like a, a calendar.

A calendar?

Yes.

Because there was no written language, correct?

No.

Well, what I find fascinating about this is how your family has kept the history through the ages.

Here we have the drawings that your great-great- uncle did.

Great-great-uncle, yes.

And there are three pages starting from about 1802 right up into the early 20th century.

Yes.

And we have in the book close to you some language in Sioux.

Is that correct?

In Oglala?

Yes, yes.

And who did that?

My aunt and my mom.

And they were little girls when they...

When they... ...used to ask him about what he was drawing.

And then they did a copy of the drawings here, is that correct?

Yes, on a, on a skin, yes.

This is a 1935 rendition of these original drawings we're looking at here.

Yes.

And I also think this is terrific.

Your family published this book, is that correct?

Yes, my aunt and my mother... What, in, in what year?

Uh, 1969.

Well, what we have here, if we can refer, in the year 1847, it would have been written in that book...

Yes, his... ...in the 1960s, the literal translation.

And if we look here, it says in 1847, "Many broke their legs that winter."

Yes.

So that would have been the event, remembering a number of years later...

Yes.

Perhaps it was a very icy winter.

Yes.

There would have been a reason why many people broke their legs.

So then 1852, "The snow was deep, a man sneaked in, and they killed him."

Yes.

(chuckles) So maybe one of their enemies?

A different tribe?

Yes.

This is terrific.

Not only the fact that this is the history here, but successive generations of your family have kept this, and not only kept it, but added to it.

Yes.

Well, the value of this, in terms of economics, is not so much money.

If you were to sell this, and I can't imagine you ever would, but if you, if you were, the value would be somewhere in the neighborhood of $6,000, maybe $8,000, mostly for these glyphs and images.

The amazing thing about this is how you and your family have kept this up.

I applaud you for doing this.

Thank you.

WOMAN: It was given to me from my mother.

My mother was a German countess, and her ancestors started in Russia, and then during the Russian Revolution, they fled to France.

APPRAISER: Okay.

And at that time, they were supposed to have acquired this piece.

In France.

In France.

It was supposed to have belonged to Marie Antoinette.

That's the story I got from my mother.

My mother was born in France, and then they moved to Germany, and she was raised in a castle in Munich.

You have five beautiful Burmese rubies here.

They're roughly somewhere around four carats, maybe four-and-a-half carats.

Wow.

In the trade, we call the best rubies pigeon blood-red rubies, and that's what you have here.

Wow.

They're bright, and they're not treated, they're natural.

And you know the bracelet was made in France.

I... was assuming that it was.

Oh, okay.

Since my mother told me that it was Marie Antoinette's, but...

Okay, well, Marie Antoinette never saw this bracelet.

Okay.

(chuckles) The hallmarks, the double eagles in the head, tell you it was made in France... Mm-hmm.

...and it's 18-karat gold.

The gold is on the reverse side.

If you turn it over like that... Uh-huh.

...you see the yellow gold.

The top, all the diamonds, they're very tiny full-cut diamonds.

They're set in platinum.

Okay.

So this is late 1800s when it was made.

Okay.

Now we... Not Marie Antoinette.

(laughs) Not Marie Antoinette, she could never wore it.

No.

You ever wear this bracelet?

No.

My mother used to wear it all the time.

In fact, she left it in a car that my father sold, and she realized that she had left it and went back the next day, and it was still in the glove box, so, uh... Oh, my God.

(laughs) (laughing): I guess I'm fortunate to still have it.

A piece like this in today's market could easily sell for somewhere between $30,000 and $35,000.

This piece?

This piece, at auction.

I'll hold on to it for a long time, then.

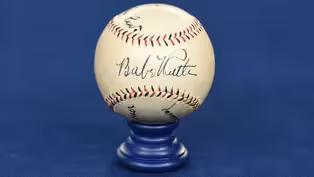

(both laugh) MAN: I was out in the mid-'90s visiting my grandmother, introduced me to her latest grandson.

And she asked me if I still played baseball, and I said I did.

She held her finger and she went into the back room.

We heard some drawers opening and closing.

She came back, she tossed me the ball.

And I looked at it and I was, I, I couldn't believe what I was seeing.

I asked my mom, "Is this real?"

And she said, "I've never seen it before."

So, uh, my grandfather actually met these individuals, uh, in the mid-'30s, and it's been sitting in a drawer ever since.

So how did your grandfather meet them?

He worked for the cruise lines, the State of California, inspecting cruise ships.

These guys were either coming back or going to Hawaii from the Port of Los Angeles.

Your grandmother put it in a letter for you.

She did, she wrote it down.

She described the, uh, cruise lines and, uh, what he did.

When was, we were reading your letter before, we noticed it said the Lore Line.

Well, Babe Ruth only took a couple of trips abroad.

In 1933, he actually traveled to Hawaii for an exhibition game, and we believe that this ball was signed in 1933.

Okay.

By Babe Ruth.

Okay.

And also by Hall of Famer Honus Wagner and Al Simmons.

Honus Wagner, the great shortstop for the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Right.

Al Simmons, great outfielder for the Athletics.

Right.

Interestingly enough, there's also a George Earnshaw signature on here.

He was a great pitcher for the Athletics, as well, who later went on to the White Sox.

We have a few mysteries about this baseball.

We can fill in some blanks, and we're going to have to give some conjecture about this.

In 1933, Ruth was winding down his career with the Yankees, and he had been bugging the Yankees for years to be a manager.

I found a 1947 article that they quoted Ed Barrows, the general manager of the Yankees, saying, in October of 1933, Ruth approached him and said he had made a deal with the Detroit Tigers' owner, Frank Navin, to hire Ruth as the manager.

He said, "You should take a train to Detroit right now and sign that contract."

And Ruth said, "Hey, I'm go, I'm doing a couple "of exhibition games in Honolulu.

When I come back, I'll sign the contract."

Well, he went to Honolulu.

When he came back, Frank Navin had already traded for Mickey Cochrane to be the next manager of the Detroit Tigers.

Oh, no.

And he said, declared, many times in his ca, after his career was over, it was the, his greatest disappointment in baseball.

Oh.

Because he was a coach, but he never became a manager.

Okay.

We're not sure if the other players went with him on the trip or not, because we can't find any proof.

But I'm going to tell you about the second thing that makes this special, which means whether the players went with him or not doesn't matter.

Okay.

It looks like it was signed yesterday.

It does.

I've seen thousands of Babe Ruth baseballs, and this one, on a scale of one to ten, is a ten.

Wow.

The Honus Wagner.

This is a ten.

The ball is an eight.

It's creamy, it's beautiful.

It's red and green stitching, which they only used to 1934.

You add this all together...

Yes.

...and you put an insurance value on one of the most spectacularly signed baseballs we've seen by Ruth and Wagner, the first class of the Hall of Fame in 1936, I'd insure this for $30,000.

Wow, you're kidding.

That is fantastic, thank you.

Are you surprised?

I am shocked, I am floored.

I have been told that it was attributed to an artist whose last name was Biggi, B-I-G-G-I, and he was a minor late Renaissance painter.

How did you get this?

I had always admired it in my aunt's home, and she was downsizing, and had contacted a museum in Florida, and I guess they weren't as friendly as she would have hoped over the phone, and decided to give it to me.

And you've had it restored at one point?

Uh, she did.

She did.

Uh, this is the way I received it.

Okay.

Well, we don't have many Old Master paintings on the "Roadshow," because we don't see too many.

And secondly, we don't often put them on because we don't often know exactly who they're by, but I think we can find out who this one is-- this is actually a, a Florentine painting of the High Renaissance.

This painting was probably done around 1500.

Oh!

The artist named Biggi, there's a Fortunato Biggi, who actually is a later, 17th- century painter, does flowers.

Mm-hmm.

That's not him.

Okay.

It's an Italian Renaissance painter by the name of Franciabigio.

1484 to 1525 is when he lived.

Wow.

This one is a, a Florentine Madonna.

He was clearly influenced by Raphael.

You have this figure here, this sort of, uh, figura serpentinata, the Christ child.

And then you have the mother up here.

It's of the period, and we can tell by the very distinctive craquelure here.

There's a very squared-off kind of craquelure, which is very much of the period.

It's not a copy.

We also see that it's on an old panel.

We have this line down here, which is not a split.

It's where the panel was joined to make this large piece of wood.

When it got restored, unfortunately, somebody wrapped it up in bubble wrap.

There's little dots here where the varnish was still wet.

At some point, you may want to redo that varnish, but here you have a great painting.

Do you have any i, idea of what it's worth?

There was a figure on the paper when I received it, but I just thought that was maybe just for insurance purposes.

Mm-hmm.

And that figure was $15,000.

Yeah.

But honestly, I don't know.

Well, in the Old Master world, we don't always know, 'cause they aren't signed.

If this painting were attributed to Franciabigio meaning we aren't quite sure, it's worth $15,000.

But if we can prove that it's real by showing it to the proper scholar in, in Italy, and if this is really Franciabigio, which I believe it is, it's worth $60,000 to $80,000.

(laughing): Oh, my God.

Oh, she'll ask me to send it back.

Yeah.

(laughs) I... Well, I'll keep it forever, I mean, I... Yeah.

I love the painting, but... No, it's a, it's a great work.

It's one of the best Old Master paintings I've seen come into, uh the "Roadshow."

It really is?

Yeah.

Oh, wow.

PEÑA: Thanks for watching this special episode of "Antiques Roadshow."

Follow @RoadshowPBS and watch us anytime at pbs.org/antiques or on the PBS app.

See you next time on "Antiques Roadshow."

Appraisal: 1873 California Gold Quartz Presentation Cane

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 44s | Appraisal: 1873 California Gold Quartz Presentation Cane (44s)

Appraisal: 1900 Mark Twain Letter

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 1m 20s | Appraisal: 1900 Mark Twain Letter (1m 20s)

Appraisal: 1903 Colt Single Action Army Revolver

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 2m 17s | Appraisal: 1903 Colt Single Action Army Revolver (2m 17s)

Appraisal: Benjamin Greenleaf Portraits, ca. 1810

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 3m 21s | Appraisal: Benjamin Greenleaf Oil Portraits, ca. 1810 (3m 21s)

Appraisal: Concord, Massachusetts Card Table, ca. 1800

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 2m 30s | Appraisal: Concord, Massachusetts Federal Card Table, ca. 1800 (2m 30s)

Appraisal: Dalzell Findlay Onyx Muffineer, ca. 1889

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 1m 2s | Appraisal: Dalzell Findlay Onyx Muffineer, ca. 1889 (1m 2s)

Appraisal: Dedham Pottery Vase, ca. 1900

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 40s | Appraisal: Dedham Pottery Vase, ca. 1900 (40s)

Appraisal: French Campaign Clock, ca. 1790

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 42s | Appraisal: French Campaign Clock, ca. 1790 (42s)

Appraisal: French Porcelain Vases, ca. 1860

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 2m 56s | Appraisal: French Porcelain Vases, ca. 1860 (2m 56s)

Appraisal: Hiratsuka Filigree & Cloisonné Teapot, ca. 1895

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 1m 16s | Appraisal: Hiratsuka Filigree & Cloisonné Teapot, ca. 1895 (1m 16s)

Appraisal: Hopi Kachina Figure, ca. 1910

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 1m 57s | Appraisal: Hopi Kachina Figure, ca. 1910 (1m 57s)

Appraisal: Late 19th-C. Fish Scale-decorated Anchor & Dome

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 1m 8s | Appraisal: Late 19th C. Fish Scale-decorated Anchor (1m 8s)

Appraisal: Matched-pair Diamond Ring, ca. 1910

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 2m 57s | Appraisal: Matched-pair Diamond Ring, ca. 1910 (2m 57s)

Appraisal: Oglala Sioux Winter Count

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 3m 31s | Appraisal: Oglala Sioux Winter Count (3m 31s)

Appraisal: Oil Painting Attributed to Franciabigio

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 2m 44s | Appraisal: Oil Painting Attributed to Franciabigio, ca. 1520 (2m 44s)

Appraisal: Old Hickory Chair Company Rocker, ca. 1910

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 3m 14s | Appraisal: Old Hickory Rocking Chair, ca. 1910 (3m 14s)

Appraisal: Ottoman Zarf, ca. 1875

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 3m 47s | Appraisal: Ottoman Zarf, ca. 1875 (3m 47s)

Appraisal: Renaissance-revival Poison Ring, ca. 1875

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 3m 39s | Appraisal: Renaissance-revival Poison Ring, ca. 1875, in Green Bay Hour 2. (3m 39s)

Appraisal: Ruby & Diamond Bracelet, ca. 1895

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 2m 26s | Appraisal: Ruby & Diamond Bracelet, ca. 1895 (2m 26s)

Appraisal: Windsor Chair & Passport, ca. 1815

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 2m 39s | Appraisal: Child's Windsor Chair & Passport, ca. 1815 (2m 39s)

Appraisal: Diamond & Emerald Conversion Ring, ca. 1920

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 2m 57s | Appraisal: Diamond & Emerald Conversion Ring, ca. 1920 (2m 57s)

Appraisal: Ruth & Wagner Signed Ball, ca. 1933

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep23 | 3m 36s | Appraisal: Ruth & Wagner Signed Ball, ca. 1933, from Charleston, Hour 1. (3m 36s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Funding for ANTIQUES ROADSHOW is provided by Ancestry and American Cruise Lines. Additional funding is provided by public television viewers.