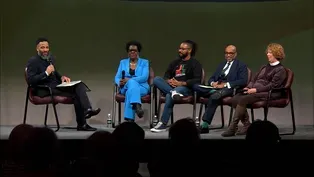

Panel Q & A – Warrior Lawyers

Special | 33m 42sVideo has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Warrior Lawyers.

Panel discussion following the film Warrior Lawyers. With panelists Emily Proctor, tribal educator at Emmet County Extension Office with MSU; Wenona Singel, associate professor with Michigan State University College of Law and director of the Indigenous Law & Policy Center; and Elise McGowan-Cuellar, appellate justice for Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians. Recorded 11/30/23.

WKAR Specials is a local public television program presented by WKAR

Panel Q & A – Warrior Lawyers

Special | 33m 42sVideo has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Warrior Lawyers. With panelists Emily Proctor, tribal educator at Emmet County Extension Office with MSU; Wenona Singel, associate professor with Michigan State University College of Law and director of the Indigenous Law & Policy Center; and Elise McGowan-Cuellar, appellate justice for Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians. Recorded 11/30/23.

How to Watch WKAR Specials

WKAR Specials is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

More from This Collection

Panel Q & A - The Cost of Inheritance

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film The Cost of Inheritance. (30m 59s)

Panel Q & A – First Voice Generation

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film First Voice Generation. (31m 2s)

Video has Closed Captions

Panel following the film "American Jedi." Discussion features the film’s producers. (48m 46s)

Panel Q & A – NOVA Science Studio Showcase

Video has Closed Captions

WKAR showcases highlights from the NOVA Science Studio project. (53m 35s)

Panel Q & A – Building the Reading Brain

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the WKAR original film, Building the Reading Brain. (36m)

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Afrofantastic. Featuring filmmaker Julian Chambliss (29m 6s)

Panel Q & A – Free Chol Soo Lee

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Free Chol Soo Lee. (29m 48s)

Panel Q & A - Storming Caesars Palace

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Storming Caesars Palace (25m 19s)

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the episode Afrofuturism, from the Artbound series (33m 56s)

Panel Q&A - Brenda's Story: From Undocumented to Documented

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Brenda's Story (25m 44s)

Panel Q & A - Benjamin Franklin

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Benjamin Franklin. (21m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Unadopted. (31m 45s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(Speaking in Native Language) My name is Emily Proctor, tribal extension educator.

I am a citizen of little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians located tip of the mitt Harbor Springs.

For those of you tuning in for the discussion, we have just viewed the one hour documentary Warrior Lawyers.

Information about ways to review the film can be found on Warrior Lawyer Warrior Lawyers.org.

As tribal extension educator, my projects include the development delivering evaluation of educational programs in the areas of tribal governance, diversity facilitation and youth leadership.

I just introduced myself in Anishinaabemoin, which is our traditional language and as an Odawa woman, I identified myself by our traditional name that I am recognized in our community as Strawberry Woman.

I am part of the Eagle Clan and when I move around in a Anishinaabe territory, I am able to say, Well, I am Eagle Clan, and if I meet another person who is also Eagle Clan, they are considered my family and relatives.

And so that is one way how we identify who our family and relatives are.

And I also share that I come from Cross Village in Lansing.

So my family typically historically comes from Cross Village, which is in tip of the mitt, if you will, of Emmet County.

You may also be familiar with Harbor Springs.

And so those are in the homelands of little Traverse Bay Bands, which again is our tribe.

And that's where I currently reside with my significant other two dogs and a cat.

All right.

Well, it is my pleasure, my deepest pleasure to introduce our panelists for this evening.

Wenona Singel, who is an associate professor of Michigan State University College of Law and director of the Indigenous Law and Policy Center and associate professor, professor of law.

She is a member of the little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians and Associate professor of law at Michigan State University, College of Law and the director of the Indigenous Law and Policy Center.

She teaches federal law on Indian tribes, property and other courses related to natural resources, environmental justice and indigenous human rights.

(Speaking in Native Language) for being with us.

We also have Elise McGowan-Cuellar.

She is an enrolled member of the little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians and serves as an appellate justice for our tribe.

In addition to her role as Appellate justice, Justice McGowan -Cuellar also serves as executive in-house counsel for the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians and President of the Board of Directors for the Uniting Three Fires Against Violence.

Again, for being with us this evening and welcome (Speaking in Native Langauge) Alright.

And also as we go through our questions this evening, you have paper and pens in front of you and will be having Emily and potentially others collect those from you as we go right to start.

Let's let's start with Wenona.

Since its release, how would you describe the impact of the film on Native American law and policy?

I would say I'm really I'm really grateful to the filmmaker because it's really been able to, you know, share information about tribal courts, but also about the history that our tribal communities have experienced and what we are doing to heal from that history and what we're doing also to grow and to exercise our culture and infuse our legal system with our cultural values.

And so I'm really grateful that there's more public knowledge and recognition of the distinctiveness that tribal legal systems provide within our country.

Well, and we didn't warn Wenona, so I apologize, but I'm going to go ahead with Annie BUJU Sanders Narcos, (Speaking in Native Language) So my name is Elise McGowan-Cuellar.

And like I said, I am a member of the Crane clan, so we're almost related Bird clan.

So we have that in common.

And I you know, what I took from the movie and what I think and I'm sorry, this is not exactly the answer to your question, but it made me feel very honored and blessed to be in the roles that I have and to live in the community I live in and know the people that I know because I take for granted.

Sometimes, you know, we have economic development, that we have all these opportunities that I get to know all these strong, powerful, queer work that are in my life to help me and shape me and make me a better person and help the next seven generations.

So, you know, it's nice.

I think I knew everybody in that video and I thought years people don't know about them, you know.

So it's nice to, you know, be able to see that on the screen and share my community just a little bit with everybody.

(Speaking in Native Language) I better introduce myself.

(Speaking in Native Language) So my name's is Wenona.

Okay, so, um, Lynx woman and also I'm a member of the Wolf Clan, and I currently live in East Lansing, and it's really wonderful to be here with you.

Wonderful, amazing women.

(Speaking in Native Language) All right, well, we can start with Elise down the way there.

How do you how do the issues raised in the film influence your work in experience in American Indian law?

So kind of what I've already demonstrated, you know, these are the people that are in my lives.

This is the work that I do.

So every day.

You know, as the attorney for the Little River Band, I get to come in to work and I get to help solve some of these problems and help our help solve problems, but also generate new ideas.

Because kind of what Carrie was saying in the video is, you know, we think with our hearts and our brains.

And so when I go in there, you know, and I see a legal issue, I don't just think, you know, what's the legal answer going to be?

What's going to happen in the courtroom?

But I think how is this going to impact my community?

How is this going to, at the end of the day or next seven generations or even when I get home after work and my kids are mad at me because I did something, you know, what can I or the community, So what can I do to help with that?

And, you know, and it's funny, you know, nottawasapi is where I did my internship, which for law school and we worked on the Violence Against Women Act.

And, you know, and it's something that we're trying to do right now at Little River is get that special tribal criminal jurisdiction.

And so, you know, it's just another motivator and it's something this is something I do every day.

I take it for granted.

MM.

(Speaking in Native Language) Ok, Wenona?

And so I would say also that I really relate to Carrie Whitman statement that she feels it's not just a job, it's her life.

It's who she is as a person.

And that's how I feel about it, too.

Because when you work in the field of Indian law and your Anishinaabe, I think that there's your entire family history and your reality has been shaped and so many innumerable ways by the history of colonization and by the ways in which our federal government has sat to dispossess and forcibly assimilate native people.

And so so it's very, very personal.

And in my own family, my mother was placed, put into foster care at infancy along with her.

Some of her siblings and some of our siblings grew up in foster care until they aged out at the age of 18.

But she and one of her sisters were adopted at the age of five.

After five years in Foster care for my mother.

And so I grew up always knowing that part of our family history.

But it wasn't until I was an adult that I also learned that both my mom's parents had attended Holy Childhood school of Jesus Indian Boarding School in Harbor Springs, Michigan, and I did not know that when I was young, and neither did my mother.

And and so learning about the experience of you know, how horrific it must have been and traumatizing to be taken away from your family at a very young age and to be institutionalized in an environment that was not nurturing and there was not did not reinforce each child's worthiness as a human being that degraded children and that subjected children to physical, emotional and sexual abuse, that malnourished children that subjected them to widespread chronic illness and disease was extremely difficult.

And so I can't imagine how they coped with that as adults and what sort of lives they led that ultimately led them to lose all five of their children to the state of Michigan's child welfare system.

And so that was incredibly upsetting to learn as an adult because it's not something that you learn in our in our public education system when you're in grade school or high school or even in college necessarily.

And then I also learned that my grandfather also is that his family also had lived at Burt Lake in Michigan and that Burt Lake had been burned down by the sheriff of Sheboygan County, along with a lumber speculator, to clear the area of the native presence in northern Michigan to make way for other development.

And so I thought, wow, it seems that every generation is being impacted by this experience of dispossession and removal and loss, and that also had disrupted family relationships for the community that lived at Burt Lake.

But then even the my ancestor who was elderly in Burt Lake, whose children and grandchildren lived in Burt Lake with him, he had moved to Burt Lake as a young half grown boy around the period of 1840 when he was taken in by an Anishinaabe family, the Wendigoish.

And during that period he was brought in from Lower Michigan and that was also during the period of forcible removal of native people by the US military, where the military was attempting to forcibly round up native people and they were hiding in swamps, they were trying to flee to Canada and to the Upper Peninsula.

And I think when I learned about each generation's experience, I came to realize we have so much to recognize and to learn from and to heal from in terms in our own communities.

And we have to think of the legal system as a way to facilitate that healing and instead of a way of justifying that, that harm.

And I know that there's a lot of ways in which in the Western system, our legal system is completely not up to the task and inadequate.

But within our within our own tribal communities, we do have the tools to try to support healing in ways that are consistent with our culture and values and with insight about our families and members of our community.

And so so when I think of the issues raised in the movie and how they relate to Indian law and my relation to the legal profession, I think how we have so much that we can do to try to we have to educate the broader society about this this history.

It can't be brushed under the rug anymore and we have to really advocate for healing both in the non native majority society but within our own indigenous communities.

And so that's how I think of it.

Well, I hate to be that person, but, you know, looking at the treaty language, right, and seeing those pictures of when they signed the treaty, it reminds me that my great, great, great seventh generation up uncle, I guess he would have been my sisters or my grandmother's brother.

You know, he negotiated the 1836 treaty, and here I am in 2024, 2023.

Sorry.

What?

You're when?

No, you know, I'm I'm negotiating treaty rights on behalf of our tribe.

So, you know, it's coming full circle and we're healing.

And, you know, some of these things are we're living with.

But, you know, thankfully to my ancestors, you know, we're moving forward.

We're getting that knowledge and we're taking it back.

So I just I want to put a positive spin on that because, you know, boarding school did disrupt us.

And I know you have more questions, but I just wanted you know, I saw important you know, I think that the comments that you both have shared provide a more holistic perspective as to the issues that were raised in the documentary.

So we got to hear both of those perspectives in some, it's a very dynamic life that many of us have to contend with.

So much for sharing any additional thoughts on this.

Okay, we have some questions from the audience, so I will pick one.

All right, Wenona, do all 12 fully recognized tribes use the peacemaking approach in their tribal courts?

That's a great question, because I honestly do not know if every single tribe in Michigan does.

I. I would not expect that the answer is yes, because it's a decision that each tribe has the autonomy to decide for itself.

And every tribe also is at a different stage of trying to address in a triage fashion the issues of most importance and most pressing need within their community.

And so sometimes well developed in of peacemaking is very important.

It might not be the top priority for that tribe at that time.

And so I don't know that every tribe does have a similar system in place.

All right.

But I would say I will share that.

I know Little River has a training tomorrow on peacemaking.

I'm missing it, unfortunately.

But it's okay.

But you know, little River Grand Traverse.

I think that was up.

You had something along those lines right?

So you know, I know more about our more Southern cousins, you know, but we're definitely all in different ranges trying to implement something along those lines because it just makes your community healthier and it helps the community at large.

So.

And different different scales of for sure.

Sure.

So each tribal nation and tribal court are different phases when it comes to their own peacemaking.

Thank you.

Alright.

What year was this film made and released, which we can find out for you, unless I don't recall that.

You know, I did some research and I'm just kidding.

I just not there.

It's actually there's been an update.

So, you know, Judge Maldonado is no longer our chief judge.

Joanne Cook is our chief judge at Little Traverse.

She was just recently appointed, but Judge Maldonado is now our Court of appeals judge.

So like, she's big league.

And then I know like some of the law students, they are now successful lawyers in Indian Country.

So it's been a couple of years, I can tell you that much.

And, you know, went on and I would say, why aren't we in this movie?

Like, what year was that?

I was I was I practicing law yet?

And then I was oh, I guess I had kids.

So maybe that's why they didn't ask me.

But I was invited and I said, No, you want to be on this panel and talk about it.

Got it.

Okay.

Now, now is all right.

What concerns do the three of you have about possible future challenges to equal?

Okay.

Future challenges to equal, which there's been a lot.

Yes.

Okay.

So as you may already know, the Supreme Court issued a decision this past June in a case called Haaland versus Brackeen, in which at the court held that the statute is constitutional and there were, you know, significant challenges to it, including a challenge to Congress's authority to pass the Indian Child Welfare Act.

And so in the court's majority decision, it strongly, you know, validated that Congress does have the authority to legislate in this area.

And also there were there were several other arguments that were made as well, which remain at half time to reach or discuss today.

But one of the arguments that the court did not address on the merits because it had determined that the parties who raised these issues did not have standing and were not properly before the court to raise these issues was the issue of whether the law, whether equal violates equal protection and so since the court did not reach that, Justice Kavanaugh wrote a concurring opinion in which he expressed his concern that the equal protection issue is a is a serious issue.

And he seemed to be inviting folks to petition the court in a new case to raise the issue of equal protection, where standing is satisfied.

And so that's still a huge concern because currently we have a precedent called Martin V MacQuarrie, which is an earlier Supreme Court case which held that when federal law makes distinctions that are based on someone's enrollment in a tribe or based on a tribe, those distinctions are based on that person and the tribe's unique political status with the United States, because they have a government to government relationship with the U.S. and those distinctions are not based on race.

And so because they are not deemed to be based on race, they're therefore not subject to strict scrutiny, which is a very difficult bar for parties to satisfy and requires that the government narrowly tailor the law to further a compelling governmental interest.

And so Kavanaugh seemed to say in his concurrence, looks other folks might bring this up, and it's a serious issue.

No one else on the court joined his concurrence, which may be a sign that other justices are not predisposed to want to address this issue in the near future.

But it's a big concern because if a case does squarely present the issue of equal protection, it could have much broader repercussions beyond the field of child welfare and the Indian Child Welfare Act.

It could also shake the very foundations of many other areas where Congress has legislated in Indian affairs.

So I do worry about that.

But how many times were you quoted in the Supreme Court decision?

I'm sorry, it's humility is one of our grandfather teachings, but I think we need to take a moment to realize someone was quoted in the Supreme Court opinion so cited ten times, ten times as he was quoted 7 to 10 times.

All right.

We have about ten more minutes or so for us to discuss a few more questions.

And we have we have multiple here.

So let's.

Okay.

For all of the kids, teens and college students possibly watching this film, what do you hope they learn and get out of this film?

What are your hopes?

So I guess because I'm younger, I get this question.

I'm just kidding.

No, you know, I think it's I hope my community and you know, I identify with Gtb is one of my home communities.

I'm also a little traveler citizen.

So I identify and, you know, not always me as well as, you know, as my one of my home communities.

But, you know, I want them to watch these movies and see that, Oh, I know her.

I see her all the time.

Oh, she was just here and whatever, you know, and community events and how common and normal it is for you to go to law school and then come back and serve your community.

Normal.

Yes, it's normal.

We're normal people.

We're not the scary people.

And I remember meeting the attorney at Gtb when I was a lowly server and I thought, I'm going to take your job someday.

And I thought, you know, I could do that if you can do that, I can do that.

And, you know, we need more of that in our in our communities.

And I hope that's what they get out of this through in real quick.

My previous life, I was a child protective service worker for our tribe, and I remember serving under Judge Petoskey.

He was the first judge I worked with.

And I tell you, you know, examination in court has always made me nervous.

No matter what has happened.

However, compassion and empathy, and it's wonderful to see many of my mentors and family and friends in this documentary.

So hopefully you'll get to see many of us college students.

If you do attend community events, go to tribal nations and tribal colleges, and you may you may see us there.

So, yeah, we have powwows, we have dances, we have feasts that everyone's invited to.

It's not just for the people in the community either or just the native people in the community, you know?

So it's a it's a it's a good time to come together and meet people and learn more.

So, yeah, why not?

And I'll just really echo what you were saying because, you know, I'm really one of my passions about working as a law professor is recruiting.

And, you know, helping students or helping prospective students realize that work in the legal profession is something that they could do.

I know when I was young, I didn't know anyone who had gone to college.

No one in my family or my parents circle had gone to college.

And and yet I you know, when I was in college, there was a law student who was enrolled at the same university who was native.

And she would help him.

She would come to our student meetings for our native undergraduate group.

And I thought, hey, she's she's a normal person.

If she can do this, I thought I could do this.

And and it kind of emboldened me to apply.

And and so I want other other folks who are to to realize that the legal profession is a really worthwhile, rewarding career where you can do good work that benefits other people.

You don't have to just work, you know, as a corporate attorney, you don't have to be in a courtroom all day.

You can literally be solving HR Issues most of your day or attending meetings with the community to make sure that their voices are heard.

When you enact special tribal criminal jurisdiction.

So and you both brought up a key points that you noticed others perhaps when you were in university or in the program or in documentaries that you could identify with.

And that is a similar narrative.

You had an individuals at institutions who you could work with and mentor with as well.

So folks who could help identify.

Yeah.

All right.

So I know we have got a few more few more moments here.

We have two more questions.

So one being, what would be some resources that folks in the audience, students and others could look to to learn more about Equa, to learn more about our wonderful nations here in the state of Michigan, in a nation of aliens.

What would be some books, movies, folks?

What would some thoughts?

Well, of course turtle talk which is the Elon went on to explain that one because I'm not a part of it.

I don't have publishing rights on the website.

I'm just kidding.

But tribal website.

So, you know, every tribe has a website.

I mean, our own tribe, little travelers, our website's great.

They just it's pretty new, right?

We just got it updated.

It's very helpful and has our history.

It has our the branches, our Constitution.

And it really helps you understand the day to day of what's happening and the community and then community events.

So, I mean, I always tell people, check out the tribe's website, whatever community you're in, because then you'll learn more about them.

And then there's always an education department because that is such a huge part of our communities is being educated and and they always have book suggestions.

And so it's just this is like a sneak.

And then if they don't, there's an email where you can find someone to email them and ask them for book recommendations for the community that you're in, right?

Mike Mm hmm.

Yeah.

And so I think if young people are interested in learning more about Acquire, I would also suggest checking out Rebecca Nagel's podcast, which is called it's called This Land.

This Land, This Land.

And I know I have a teen, I have two teenage sons and then, you know, I'm always surprised they'll know, you know, they'll recall all sorts of details and they'll, you know, they listen to the podcast, too, and have learned a lot about IGA because she completely focuses on all aspects of the parties and the litigation.

And in a way that's really dramatic and compelling, almost in a way that sort of a, you know, almost like a mystery that she's revealing in terms of the revelations that she makes with each episode.

And so so that's something else, another way that younger people can learn about it.

And then, of course, there's the National Indian Child Welfare Association Network, which is an Oregon national organization that has publications.

And so that's another great place to learn about it, too.

And I would say for students here, our MSU library has a great resource.

Our research guides their individuals there who are phenomenal in addition to our Michigan State University extension website as well.

You know, we've been working to update that with very relevant information from our tribal colleges too.

So a few more items there.

Okay.

One final question.

I think I could just talk with you both all evening.

We haven't had more time.

Let's just wrap the mandate up.

You could do this land Part two.

Yes, Agent Niche.

This land needs you.

Throw a little language there.

Okay.

We can do a nation of a dream, right?

I can do that.

However, I'm great.

What can law schools across the nation do to improve their outreach and access to Native American students interested in studying American Indian law?

What can we do then?

So law school locally?

Well, you know, I come you know, obviously works for the law school that I attended.

So obviously she has more input on that.

But I was thinking in terms of like undergrad and even high schools, I know my alma mater brings community members and, you know, even if they're not nationally or from the Michigan area, we bring them to powwows and so we bring them to the little Traverse band bands powwow.

That's the second week in August, if you want to write that down.

Normally.

And we have them introduced to the community and we, you know, this past year I had a special so I actually went on and I had a special this year at our powwow where we had college students helping us.

They helped pass out candy and they talked to community members and I tried to incorporate them into the the whole part of it, because that is such a big part of my life is the education I have and how grateful I am for people like Winona who got me into law school and made me stay and and this is where I am now.

So I nation wide.

All right.

And I would just say I'm also a huge supporter of developing our curricula to meet the needs of those who want to pursue this profession.

And also because everybody needs to know, everyone in the legal profession needs to understand and tribal sovereignty and the history of treaties and treaty rights and needs to understand the major issues that impact tribes.

Because tribes are, you know, governmental and economic actors that have relationships at all levels of government and with all sorts of other economic actors in society.

But also, I just want to bring it back to the fact that Michigan State University in particular is a land grant university.

And that means that it has it is the beneficiary of the dispossession of Native people where Native people entered into treaties for the session of their lands in exchange for a multitude of other promises and compensation.

But that compensation by the end of the 19th century resulted in about $0.14 an acre.

So just profoundly and under compensated and of course also under circumstances of extreme duress and coercion.

So I think it's very important that as a university, we recognize that we're the beneficiary of that dispossession, and it should inform how our commitment as a as an institution to build respectful relationships with native nations.

And also it's consistent with the with the dictates of the moral act that we democratize education and provide services to the public at large.

And that includes identifying the educational needs of tribal communities and being sure that we have programs and courses, curricula, curricula, and also faculty with expertise in areas of relevance to the needs of tribal communities.

So I think that those are all really important aspects, and we do that at the law school, went through the courses we offer as part of our Indigenous law certificate.

But I would like to see that, you know, sort of, you know, at all of the various parts of the university and to be clear, not just native people, it was our people.

Those are our ancestors that gave that up.

And and MSU was law school was always where I wanted to go because of the Indigenous Policy Center.

I never wanted to go anywhere else.

I never wanted to leave my community in the first place.

But I knew if I was going to, I wanted to come to a place where there were strong bonds and a family that I could have outside of my regular family.

And then I knew I would have the education that I needed to go back to my community and make it better.

And of course, while the University of Michigan is not technically a land grant university, it is the beneficiary of a grant by the tribes because the tribes entered into a treaty called the Treaty of Fort Meeks, in which they specifically provided land for the formation of a university that ultimately became the University of Michigan and in the Treaty of Fort Means, our ancestors stated that they gave they provided this grant because they wished for their children to be educated.

And so I do.

That's all we are.

Strongly believe that our universities have commitments and responsibilities is as well.

Like I said, I would love to have more time with all of you, in particular these two wonderful Kwe that I am able to work with.

No.

And speak with you this evening and share with all of you.

(Speaking in Native Language) For being here with us for taking time away from your loved ones, the communities that you serve, and to sharing yourself with us this evening.

(Speaking in Native Language) All right.

Well, that is all the time we have this evening.

We go to our panelists and again, we go to all of you for joining us for the warrior lawyers presented by the Native America Institute.

And W are events like this from air made possible with support from people like you?

We go back to those who have donated to WKRN again, we watch.

Have a wonderful evening and safe travels to your destinations.

Kind of going out (Speaking in Native Language)

WKAR Specials is a local public television program presented by WKAR