Panel Q & A - Poisoned Water

Special | 42m 7sVideo has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the NOVA film Poisoned Water.

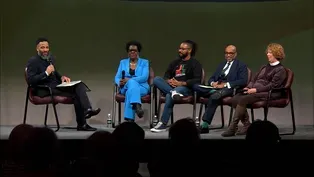

Panel discussion following the film: Susan Stein-Roggenbuck, Ph.D., James Madison College. Mieka J. Smart, DrPH, MHS, Division of Public Health / College of Human Medicine. LeConté Dill, Ph.D., Department of African American and African Studies. Erik Ponder, MSU Libraries, is the moderator.

WKAR Specials is a local public television program presented by WKAR

Panel Q & A - Poisoned Water

Special | 42m 7sVideo has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film: Susan Stein-Roggenbuck, Ph.D., James Madison College. Mieka J. Smart, DrPH, MHS, Division of Public Health / College of Human Medicine. LeConté Dill, Ph.D., Department of African American and African Studies. Erik Ponder, MSU Libraries, is the moderator.

How to Watch WKAR Specials

WKAR Specials is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

More from This Collection

Panel Q & A - The Cost of Inheritance

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film The Cost of Inheritance. (30m 59s)

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Warrior Lawyers. (33m 42s)

Panel Q & A – First Voice Generation

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film First Voice Generation. (31m 2s)

Video has Closed Captions

Panel following the film "American Jedi." Discussion features the film’s producers. (48m 46s)

Panel Q & A – NOVA Science Studio Showcase

Video has Closed Captions

WKAR showcases highlights from the NOVA Science Studio project. (53m 35s)

Panel Q & A – Building the Reading Brain

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the WKAR original film, Building the Reading Brain. (36m)

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Afrofantastic. Featuring filmmaker Julian Chambliss (29m 6s)

Panel Q & A – Free Chol Soo Lee

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Free Chol Soo Lee. (29m 48s)

Panel Q & A - Storming Caesars Palace

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Storming Caesars Palace (25m 19s)

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the episode Afrofuturism, from the Artbound series (33m 56s)

Panel Q&A - Brenda's Story: From Undocumented to Documented

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Brenda's Story (25m 44s)

Panel Q & A - Benjamin Franklin

Video has Closed Captions

Panel discussion following the film Benjamin Franklin. (21m 46s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- Good evening and happy New Year.

My name is Erick Ponder.

I am the African and US Ethnic Studies Librarian at MSU Libraries.

I would like to welcome you tonight and hope you are safe and well during these difficult times.

No matter the venue, it is great that we can come together to launch a full week of activities commemorating the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

This year's commemorative theme, chaos or community, is based on a 1967 book by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., "Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?"

Advocating for human rights and a sense of hope, it was King's fourth and last book before his 1968 assassination.

King believed that the next phase in the movement would bring its own challenges as African-Americans continued to make demands for better jobs, higher wages, decent housing, and education equal to that of whites and a guarantee that the rights won in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 would be enforced by the federal government.

He warned that," The persistence of racism in death and the dawning of awareness that Negro demands will necessitate structural changes in society have generated a new phase of white resistance in the North and South."

On behalf of WKAR, MSU Libraries, and the 2022 MLK Planning Committee, we welcome you to the final evening of the second annual Five Nights Towards Freedom film series.

For the past four evenings, we have screened emotionally powerful and thought provoking documentaries and films, and this evening we continue that cinematic journey with the screening of the documentary film "Poisoned Water."

Before we get started with the discussion, I have a few quick housekeeping notes.

Events like this from WKAR are made possible with support from people like you.

Thank you to those that have donated to WKAR.

If you're not a WKAR donor yet, you can do so as the donate to WKAR link on this page or call 517-884-4700.

For tonight's discussion, please enter your questions for our panelists into the comment box, and I'll put them to the panelists as time allows.

Now it is my pleasure to introduce our panel for tonight, Dr. LeConté Dill, Department of African American and African Studies, Dr. Mieka J.

Smart, Division of Public Health, College of Human Medicine, and Dr. Susan Stein-Roggenbuck, James Madison College.

I'm going to open up the conversation with just getting your first impressions of the documentary, Dr. Stein.

- I think what strikes me when I see the film, and this isn't the first time I've seen the film, is how many people and how many specialties, how many organizations it took to get people to pay attention.

From LeeAnne Walters, you know, a mom who's trying to, you know, make sure her kids are safe, to other community activists, to Marc Edwards at Virginia Tech and all the students he mobilizes, as well as Mona Hanna-Attisha, who was able to track the blood levels, but the amount of effort it took to finally get people to pay attention and to recognize that they had a colossal public health crisis and the incredible human toll that it took.

That's what struck me as I watched the film again.

- The word that I can conjure up for myself was just immensely frustrating.

It was a very frustrating documentary to get through.

Dr. Dill.

- First, I'd just like to say, thank you, Mr. Ponder, for this invitation to be on this panel, and thank you also, WKAR, for the support.

This is the first time, me seeing this film.

I of course knew about the crisis, but I'm new to Michigan, been here only a few months, and I think being so close to the crisis also feels different, but the film made me mad.

It made me mad, and it made me sad.

Nothing new, I think it's unfortunate what happened, but a lot of the mistakes, a lot of the negligence.

Again, we heard in the movie, you know, that they were learning from Cincinnati.

They were learning from DC.

So the things that were happening contextually has happened before in this country, but also the missteps and mistakes by political players have happened before, so it's unfortunate that we haven't learned from the mistakes.

We haven't learned from the lessons.

We haven't listened to the experts, whether they be people in communities experiencing the outcomes or scientists that are trained to track the outcomes.

So it made me upset, and I think it's good to be upset 'cause hopefully that type of upset, that anger, even that sadness will spark action.

- Thank you.

Thank you so much.

And Dr. Smart, you're based in Flint, so it must really hit home for you.

- It hits home from me in a way that...

I have to admit right now I moved to Flint five years ago, and the water was switched about five years ago.

The water was switched in 2015, and that was before I arrived.

So there is some distance from the trauma that I have, but I am a witness to a couple of things that I was reminded by in watching the film.

And the first is that, towards the end of the film, two pieces of information were revealed, that it was going to take about $1.5 billion to really remedy all of the health concerns that they knew people were going to have going forward.

On November 11, 2021, a settlement was reached.

Back when that film was created, nobody knew, but the estimates were around 1.5 billion.

About a third of that is what the settlement turned out to be, only a third, and people here are devastated.

People know that their kids and their kids' kids are going to have ongoing problems from this that they can't even begin to cover financially, right.

Okay, the second thing, 'cause I'll stop talking about them.

The second thing is that, at the end of the film, they talked about the fact that the biggest lingering problem was probably going to be mistrust of government, and that mistrust is so well-deserved, those politicians earned it, and the mistrust is, it's so deep, and it's probably going to be the most debilitating force in Flint going forward because the people of Flint know lots of folks were paying attention.

They were paying such close attention that they were deliberately doing coverups.

So people were paying attention.

They were just trying to undo what they know they had damaged.

And so that mistrust and the fear of the unknown about what's going to happen with me and my family health wise and the knowledge that something will happen, but I just don't know what, and I know I can't cover it financially, this is going to impact Flint for decades.

- Thank you so much.

That's, again, just very difficult to watch and try to understand.

And another piece for me of attempting to understand the situation was why the coverup?

What did they think that the coverup would work, and why did they stay with that program for so long?

I'm just opening that up to anyone.

Any thoughts?

- Well, they weren't counting on that one woman.

I don't remember what her name was.

I'm so sorry I didn't write it down while I was watching the film, but she were for force.

- LeeAnne Walters.

- They were not counting on Lynn, and Lynn's love of her own kids and the kids in her neighborhood.

They were not counting on her connections and her persistence.

That woman is incredible.

- And holding people accountable.

She was asking for specific documents, specific tests, specific data that, like you said, they were not counting on that, right, for her to be an expert and to hold them accountable.

- And to know who to go to when she needed to get something out, whether it was Del Toral with the DEQ, who was later called a rogue employee, for the report, or Marc Edwards, but her ability to reach out and asked for help, and yeah, she's a fierce advocate.

And what really strikes me in the film too is it towards the end when she says my kids will never drink, use water out of a tap again, right.

Speaking to your point about trust and mistrust and the damage that does, as, you know, we're in the midst of COVID, and we need to be able to trust science.

We need to be able to believe the science we're being told.

And when I've watched the film again, I thought about that, and I thought, wow, the profound effect, the long-term effects of that, that loss of trust or exacerbation of loss of trust.

- Yeah, one of the last quotes from the film, once you corrupt science, you corrupt your agency.

And there were many agencies that corrupted themselves in this film, but as you said, in this era of COVID, we're in the same moment, right, of discounting of experts but then a distrust of being in the midst of that political turmoil of major distress and warranted.

- So please correct me if I'm wrong, a sense that I received out of the film as well was a local, regional, and national type of feeling of, and as you mentioned also, Dr. Dill, of these agencies.

So how does that come into play, if it does at all?

- I mean, everyone, please chime in.

I think we all have experience with that, right, but there are multiple actors at play, right.

And I think this film begins to illuminate the various players and the type of power analyses that we need to do when making decisions, when holding people accountable, but in also doing research.

And so no matter, you know, what we're teaching like at the university that political, that power analysis is necessary.

So you have city, county, and state health departments.

You have environmental agencies, so the EPA at a national level, but then the EPA also has regional offices.

You have the state environmental agency, but you also have the mayor, but then the city was then taken over by emergency managers, so there is mayoral and also other agencies, other staff, other offices were taking over.

So you have, again, mistrust, distrust, different types of control.

Who do I go to?

Who do I listen to?

Who has power?

And let's unpack what power means, right.

Access to dollars, access to budgets, right.

So you have all of that going on.

- And it was the governor sued?

Was there some lawsuit against the governor as well?

- I believe he was named in a suit, and they did try to pursue criminal charges.

They were later dropped, but he was offered a position at the Harvard Kennedy School, and whoa, the backlash.

I mean, they withdrew the offer, and Dayne Walling, who was mayor, right, was voted out.

Although, as Dr. Dill pointed out, with the emergency manager in place, local government didn't have a lot of power.

And so he was unable to make decisions, but he too was viewed as complicit in this.

So I think it's just- - He drank the water.

- Go ahead.

- Remember he- - He did, he did, yeah.

- To convince everybody that the water was okay when they knew that it wasn't by taking that sip.

And then you asked about a national influence, unfortunately, President Obama did the very same thing, at the end of the water crisis, came to Flint and then took a ceremonial drink of the water.

And everybody's like, look at this.

- Yeah.

- Well, we've seen this before, and we know not to trust it.

- Well, and I think that the layers of, I mean, you think you have all these agencies, all these levels, and then you think some would be a check on another, and the pervasiveness of that failure and this deliberate hiding of what was going on.

And I think Dayne Walling made a really important point when they started to read all the information that Edwards got through the Freedom of Information Act, and they said, you know, I can't remember the exact quote, but is Flint a community we want to really fight for, right, which is just horrifying and, again, feeding that mistrust.

And you know, now we have Benton Harbor, right, that's facing similar issues, and we just don't learn, and some communities are valued, and I think some are not, and this is a vivid illustration of that.

- Still waiting for our first question from the audience.

So please, please send us some questions, and we'll definitely address them.

So I'm gonna move on to another question I have for you, ladies, and that is, is lead in a drinking water an issue in other communities?

And I know that it was touched upon a little bit in the film when they mentioned Washington DC and their history as well.

- It's a problem across the country.

A good part of the United States has an aging infrastructure.

And when you think about where we sit on the Rust Belt and what that means for the cities that are all along the way, all the way to the east coast, I think it's a problem that you want to think that folks that are watching and saw what happened in Flint would not let that happen again, but the problem isn't necessarily the infrastructure or the water source.

The problem is not necessarily the testing, was it done right or done wrong?

The problem is people.

People are the problem here, right?

It's not that nobody picked up on it.

It was detected pretty early.

People are the problem, and if people continue to put their whatever their values are in front of protecting the people that they have been voted in to serve or that they were hired to protect, then this is not only going to be a problem with regard to lead, but like just protecting lives generally.

- I know nationally many local health departments have a lead prevention staff person or office, but I know that they have less capacity.

So it's less staff, less funding than other departments.

And again, because if we just look at it as a lead issue versus a community health issue, then we're not really treating the problem at hand.

- Okay, we have our first question from the audience, and it's from Dr. Eunice Foster.

What role did our two major Michigan universities, MSU and U of M, play in investigating what happened in Flint?

Why did they have to turn to Virginia Tech?

- I think that Virginia Tech is where the professor was that had done this work before in DC.

So he was an already expert, and like he said in the film, he knew where the bodies were buried.

He knew exactly what to request in terms of FOIA requests that would uncover the entire plot, and so he did exactly that.

He also pulls in his younger counterparts who are able to do other parts of the investigation that he wasn't working on, and he pulled in students that flooded Flint, but it was Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, who I think we're all proud to say is a Michigan State University faculty member, and she's the one who really provided the undeniable proof with blood levels, blood lead level samples.

And then with geographic analysis, it was really undeniable proof that what they had been saying from Virginia Tech all along was true.

So I don't think it's that the universities here had nothing to do with it.

It's just that, you know, everywhere there's not an expert about everything, and that specific expert happened to be elsewhere.

- Thank you.

- And Edwards, as you said, was able to hit the ground running and knew exactly what to do.

And Hanna-Attisha was so pivotal in this, and the fact that she was friends with Betanzo I think what's her name, the woman who had experienced in DC, and they were having dinner one night.

Hanna-Attisha writes about this in her book, and it happened to come up, and that mobilized both of them.

And then Hanna-Attisha was able to tap into the medical infrastructure that she had access to, you know, the blood samples, to Flint hospital, and could get the data to prove that this was devastating.

- Again, again, I think it's, again, a demonstration of the fact that people kept that plot up for so long it took a network of people to bring it down.

And so I think that that's the struggle, and I'm just really, really glad that Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha actually had the stamina to withstand the entire amount of research that had to happen and then withstand the backlash.

And I don't know if others truly know how much came her way in terms of hatred, threats against her family, all kinds of stuff that she's had to deal with and has remained strong and brought millions of dollars of support, not research, support for Flint families in lots of different ways to Flint.

- Dr. Dill, would you like to jump in there, or?

- No, I think they both covered it, and I think that's a great point that you mentioned around the backlash because being trained as researchers and scholars, right., we aren't always, unless we're politically savvy, right, we aren't always trained to what about that backlash, right, how to respond to it, how to stay healthy or set boundaries when we get it, and then what support do we have institutionally when we get it, so I think that's a very important point to like, raise and herald her, but how can we learn across the university because other types of backlash might come our way, even with the most rigorous science, right, and how can we support one another and then work, like you said, the support that she garnered wasn't for the research, but it was for the three families that needed it most.

So how can we galvanize more resources for that kind of effort?

- And in this case, what just struck me as interesting, and I'm just thinking of this now, is that she wasn't the first one in this scenario to receive that backlash because the story of the faculty member from UVA that came and started the samples started with backlash from his work that he had done in DC.

And they said that it turned him into like a fanatic about it.

Like, he just couldn't stop thinking about it.

He became obsessed with the fact that things like this get covered up.

That became his super power, and that super power, he used it as a function to help the people of Flint.

And I just, I think that it's a really interesting reminder that, you know, when you're up to something good, you'll have to resist a lot of really hateful things, but on the other side, a lot of people can benefit from it.

And in this case, he saved lots of lives.

The city of Flint has 95,000 people in it right now.

Lots of lives were saved.

- Before we move on to the next question, can we just publicize Hanna-Attisha's book?

What is the title?

What's the title of that book?

- "What the Eyes Won't See," or "Don't See."

It's a memoir about Flint, but it also is her family story, and it documents really nicely, as Dr. Smart was saying, the backlash that she was not prepared for, the attacks on her professionalism, her credibility, as well as just the personal.

It's a powerful book.

- Thank you, Dr.. Moving on to the next question from Hannah.

What happened to the public health officials in Flint after this was all over?

Were they actually held accountable?

And I know they covered a little bit of that in the film with one of the major.

- Yeah, they covered a lot of it in the film.

You know, it's interesting because public health officials in Flint, the municipality of Flint, don't have a lot of control over what happens with the water.

You might remember that the problem was with the state.

The state where the folks that really had control over how the water was handled, how it was treated, everything.

So public health officials that, you know, did the work of like, you know, helping to educate the community or saying, yes, we think the water is safe now because that's what we've been told to say, I don't know if they were a part of the coverup.

It seemed like it happened at the state level.

The folks in the city of Flint that were held accountable were the people that had been kind of brought in as oversight once the mayor was removed, and I think that that was covered in the film.

- The emergency manager, I know was charged.

Others were charged.

I don't know that any of them actually ended up really facing any- - Jail.

- Jail, no.

And I have to go and look at what actually happened, but in fact, the one employee who was fired over it, I think it might've been in the DHHS, just won a settlement for back-pay because they said he was fired unjustly.

But so the accountability, I don't think was there in terms of our justice system, if you want to use that term, but there were efforts, and as I said, I think the political cost to people, including, you know, the governor, was pretty high, but, you know, again, it doesn't...

I guess, how do we keep this from happening again?

As part of that, I think is holding people accountable, and having consequences.

And I'm not sure there were...

There weren't enough consequences.

- And it's a really important point around the impact is hyper-local, right.

This is happening to residents in Flint, but the actual access of power is not at the city level.

And I think that happens across the country, and again, us understanding where the power lies, the access to resources, and that's a national issue in this country.

I just moved from New York City.

If we think about the subway system in New York, which is always in the news, very hyper-local, but it runs through the city, but it's not governed by the city.

It's actually governed by the state, right, and like, not a lot of people know that.

So there's a lot of agencies around the country that, again, have this hyper-local outcome, but the governance is at another level, the county or the state or even national players that kind of have their hand in control.

- And this did draw attention to the emergency manager system that had been implemented.

And that has not yet been undone, but there are efforts to undo it.

And that removal of what little power local people have was critical in this because they weren't able to make decisions, and then they were relying on the state experts for the data, which was not being reported accurately.

- Sorry.

We have another question, and it's from Andy.

And as we pair aging infrastructure with greater climate volatility, more severe weather events, and large stage capitalism, what should we be doing as communities and as universities to avoid similar crisis?

- Man, it's such a big question.

Like, what is love?

That's how the question feels.

But, you know, I think that, so often, decisions are made by looking at the bottom of the balance sheet, right.

Like, how are the shareholders going to see this number that's at the bottom?

And until we're able to shift the decision-making from that type of value system to one where we're looking at the children, right, like let's look at the kids in kindergarten and think about them and their children.

And when you think about that, and you look at climate change, and you look at our infrastructure, and you realize where we're headed, to me, it's difficult to not snap awake and you know, not change the value system.

I don't know how to do that.

That's why I said it's so big.

It's like, what is love?

Because how do you get people to stop thinking about greed and think more about human humanity?

I don't have an answer to that question, but I do know that's what it takes.

- I think part of it is what Andy is detailing even in the question of putting the people that are concerned with these issues together in the same spaces.

So oftentimes in the state but nationally, public health is a different agency from mental health, which is a different agency from environmental quality, let alone environmental health, right.

And if we think about capitalism and then climate change, right, it maybe part of some public health discussions it might not be.

And then thinking about capitalism or other oppressions, some folks are having that analyses, and not enough folks are, right.

Or folks just started having that intersectional analyses last year or a couple of years ago.

But if we kind of get out of those, what folks call silos, I think that will help, and not just in the conversations like this, which is really important, but at the decision making tables.

So not only are those separate agencies, those are often in different parts of the city or the county.

Those are different budgets.

Those are often also different types of data collection systems.

So folks are not even crunching numbers in the same way, so they're not even able to talk to one another, let alone pool resources.

So I think it really is having this intersectional analyses of the systems of power, but also the systems of oppression.

- Well, and I think using...

This is the fault of this.

I mean, this is a key issue with this whole situation is they're not listening.

They're not paying attention to what's happened elsewhere, and they're not learning.

They're just doing the same thing over and over again.

And I think Dr. Smart's absolutely right.

What motivated the switch to the water was not the water quality.

The water was fine.

It was money.

It was a budget saving measure that had very tragic consequences, and it didn't have to.

So I think it's a combination of getting people to talk to one another, I think that's really important, but also just simply recognizing what's happened before and preventing it.

You know, with DC and now with Flint and now with Benton Harbor, this problem is everywhere.

There's lead lines all over the country, and very few cities have replaced them.

And that's just, you know, like Andy said, it's linked to so many other issues, and we're going to see problems like this, complex problems.

- I forgot to mention that the pipes have not fully been replaced yet.

- No, they have not.

- So we're still like having to divert traffic around whatever area of the city at, you know, any given month, moment, is under construction or not.

And so, yeah, it's took a heartbeat to make the decision to switch to water because of what was at the bottom of a balance sheet, and here we are, it was in 2014, and we're in 2022, all these years later, so many lives lost from Legionnaires' disease.

I forgot to mention that earlier on in this conversation.

I think the biggest, like measurable loss of life, like fatality type was from Legionnaires', and it was severely under measured because there was a real, real big spike in diagnoses of the cause of death not being Legionnaires', and it actually being due to other lung problems that year.

And so we know that a lot of that was due to the water crisis as well.

- I have another question from the audience from Audrey.

What role does GM play in terms of accountability because they use the Flint River as a dumping site, right?

And in the documentary as well... As a company, they switched away from the river water as well.

- It was corroding the parts in the plant, and so they went back to getting water from Detroit.

- It's another demonstration of how power and access to resources determines the outcome of any given group.

And in this case, the group of people being the folks responsible for the dollars at GM, like, oh no, no, we can't have this for our precious parts.

We'll go ahead and switch ours.

You know, let the others worry about how the people are going to drink water, but for our cars, we're going to have to switch our water on our own.

We cannot wait for the state of Michigan to fix this for us.

And they did what they had to do for their cars.

You know, I think that around the world, companies dump into water, and GM is no different probably.

I'd have no idea whether they dumped into the water or not.

So I can't say what role they played that way, but I do think that the fact that they were able to so quickly pick up on the problem and quickly switch it for themselves is just more of a demonstration of the same that we've been discussing.

- Well, and that was not paid attention to, right.

That was such a huge flag that there was a problem, and the same people who were ignoring it from LeeAnne Walters and Marc Edwards, that should have been a wake-up call for a lot of individuals, and it wasn't.

- But they weren't, it's like they were ignoring and like covering it up.

You know what I mean?

- Sure.

- They weren't even ignoring it.

They were deliberately trying to like sweep away the prints in the sand.

- Yeah, they talk about, in the film, willful negligence.

Some people will talk about benign neglect, but I think it is malign neglect, right, this intentional... And it's not ignoring if they know of the problem, and they're intentionally working in some people's best interests but not the greater good.

- So this is the last question for our panelists.

If you could, can you conceptualize or pull together the meaning of this film in the context of our series this week?

You know, we think about issues of race, and we really haven't talked about race that much this evening, but we think about issues of race and poverty, and we talk about policy, we discuss economics and financial issues and demographics.

So if you could just kind of contextualize, as we close, the films that we screened all this week, thank you.

- Important question.

Big question.

Another what is love question.

I mean, health is everything, right?

These decisions where you're talking about industry or deindustrialization, where you're talking about capitalism or environmental justice, these are all health issues.

And so I know health is on everyone's lexicon because of the last two years.

Some of us, it was always on our lexicon because of how we were trained, but health is an everything issue.

And I think that like the film tonight but also the whole series should remind us that we should not just care if it's in the press or if a big corporate agency or a person is being sued, but we should care because it's happening to people, right.

And in most of the films this week, we have the most marginalized, who are marginalized because of the decisions of players in this country, and because of the systemic willful negligence, they're suffering the most, but also they are the most hopeful, and they're the most knowledgeable and the most active, right.

Citizen science was the term that was brought up in this movie and in this film, but I think that was in the films all week, right, of local folks using their own experiential knowledge, let alone other types of knowledges, to make their voices heard, to make change, even being part of the film, right.

If their voice wasn't heard by the government or politicians or agencies, my words are going to be heard in this piece of art, and this piece of art could be used for action.

- Erik, from your question, I think about the fact that we're here to commemorate Martin Luther King.

That's what this film series was about.

The film that I was able to discuss was about how the stress that women experience is born out into the survivability of their kids, of their newborns.

So women with more stress give birth earlier, earlier than they should, to babies with low birth weight.

And that happens even more with Black women specifically is what the film that I got to discuss was about.

And in this case, we've got an entire city of women, who, many of whom delivered babies during this period or right after, right up until now when we're still not supposed to drink the water out of the tap.

And it's stressful.

It's stressful having to run to wherever to go get my water whenever, and I have a lot of means to be able to go get that water.

Imagine if I didn't.

And so many people here don't.

Flint was a city, and this is going to speak back to the question about GM, Flint was the city where GM was the main source of employment.

And when they pulled out as the major employer here, many, many people have been left with almost nothing, really, almost nothing.

And so it's stressful being a Flint, and then it's stressful being in Flint under a water crisis.

It's stressful, all this mistrust, and that's going to be borne out in how the babies are thriving or not.

Martin Luther King said that those who do nothing while witnessing injustice and wrongdoing do worse than those who commit acts of injustice.

The privileged have a responsibility to do what they know is right.

Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.

And I think that this entire scenario, it just really speaks back to something that he said so long ago.

- I think what I would add to that, I screened the film on Monday about the history of Medicare and how that was a catalyst to desegregate hospitals, and one of the issues we talked about in the discussion was what access to care means and that getting into the place that provides that care is the first step, but that many issues persist, and I think the film speaks to that, right.

Everyone's health should matter.

Everyone's health is not valued the same.

Communities are not valued the same, and the effects of this are going to be really longterm in that regard.

So I think it speaks to how much is left to be done and how wide ranging the effects on health are.

The idea of, you know, what these children are going to face, what the newborns they're going to face who were born during this, when their mothers were drinking the water, all of that, we won't know that for a long time, but yeah, you have to stand up and pay attention.

- Dr. Smart, Dr. Dill, Dr. Stein-Roggenbuck, thank you for this evening's conversation.

It was really powerful tonight.

I would just like to say we hope you enjoyed the presentation, and goodnight.

Bye-bye.

WKAR Specials is a local public television program presented by WKAR